Sunk within an obscure street near the city’s medina, there is little to distinguish number 18 from its rival further down the street, or the small haphazard book stands that shelter in the square opposite from a rain that never quite comes. All nestle amid the bleached awnings of the French ville nouvelle, itself marking the transition from the storied Arab architecture of the medina to the grand colonial designs of Tunis’ city centre.

Recent years have not been kind to the bookshop. Battered by changing tastes, new technology and now the pandemic, the old shop is facing closure. But with the news spreading – via social media, with no little irony – people have come from across Tunis, eager to make a purchase to help out or simply to explore this unknown part of their city’s heritage before it vanishes.

The shop itself is a layered affair. Beyond the trestle tables outside, a long alleyway takes the visitor past incongruous displays of Bee Gees albums and Magnum PI annuals. Once inside, grey steel shelves support stacks of yellowing and apparently randomly assorted manuscripts. Amid the anarchy, bright orange stickers list the names of Sartre and Zola, as shoppers drift past. Some pick carefully through the papers while others are simply content to take in the sights and smells of a freshly discovered curio.

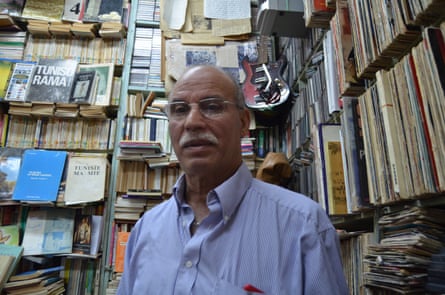

Hovering near the table that doubles as his till, the shop owner, Faouzi Hedhili, 70, hurriedly answers questions, before darting away to answer another query about the price or provenance of a certain book.

Turning his keys over in his hand, he explains how the shop was originally opened by Victor Guez shortly after the second world war. In Hedhili’s telling, Guez sold it to his father, Bouraoui, a clothier from the Medina, at some point during the 60s. Following the shop’s sale, Guez joined the growing throng of Jewish Tunisians leaving their homes to build new lives in Israel. “He really knew about books,” Hedhill remembers, recalling primary school visits to the shop where he had been impressed by the former owner’s knowledge.

“My father hadn’t really gone to school, but he was determined to maintain the business as a bookshop and spent a lot of money renovating it,” Hedhili says.

However, times have changed and, until the last few days, the bookshop at 18 Rue d’Angleterre has found itself out of favour. “Tunisians don’t really read any more,” he says, “It’s not just coronavirus, or the revolution. Even high school students aren’t interested in reading.

Faouzi Hedhili, the owner, says the 70s and 80s were a golden age for the bookshop, which opened soon after the second world war. Photograph: Simon Speakman Cordall.

For Hedhili the 70s and the 80s were a golden age, where customer numbers were such that, “We used to have to put a ladder out by the entrance of the shop to limit access. One would come out, one would come in.”

All the same, reading for pleasure remains a minority pursuit within Tunisia. Since the founding of the Tunis Book Fair in 2015 until last year, Emrhod Consulting have conducted an annual poll of the country’s reading habits. The numbers are fairly consistent. Asked if they had purchased a book other than newspapers, magazines or the Qur’an, within the last 12 months, only 10% of Tunisians polled responded positively. Asked if they kept similar books in their homes, only 26% said yes.

Hedhili returns from another of his frequent forays into the shop, “We used to sell French literature, little else,” he recalls, pointing to the shelves that still heave under the weight of French literature and philosophy. However, he says, demand is giving ground to calls for books in Arabic, with shoppers seeking books that reflect themselves, their worlds and their religion over the works of their former colonisers.

Tunisia’s economy was struggling even before its 2011 revolution and the pandemic has hit it hard. Speaking at a press conference earlier this week, prime minister Hichem Mechichi told reporters that to date, Covid-19 has cost Tunisia $2.9bn (£2.1bn). The effects are being felt on the street.